My suspicions were confirmed when she asked if she could take one of my hairs for "testing," reassuring me that it would only take a minute. I said yes. She was as excited as a puppy under a Christmas tree. She took the hair over to a device on the counter. She clamped the two ends of the hair so that it was held taut. There was a magnifying glass and ruler to measure the hair's diameter. The machine slowly and gently stretched the hair until the breaking point, just like a miniature medieval torture rack. She noted down all the data, then turned to me. Her forehead was shining with sweat, her eyes were agleam. She was breathless. "This," she whispered, "is the thickest, strongest hair I have ever measured." Then she asked if she could have another hair, as a souvenir. I said yes. I wondered what her hair collection looked like. My family also appreciates my hair. "Wire hair" they call it, with that affectionate, teasing tone of voice that family members use with each other. But I don't have a complex about my hair. Really.

|

| Gaspard Riche, the Baron de Prony (1755-1839). French mathematician and hairdresser recruiter. |

The MISPFRUH Award, for the Most Innovative Scheme for Post-French Revolution Unemployed Hairdressers, has to go to the French mathematician Gaspard Riche, also known as the Baron de Prony. He was in charge of calculating mathematical tables for a huge land survey, the Cadastre. The government was keen to have comprehensive tables, for they could be used not only for surveying (and thus taxation), but also for astronomy, engineering, and navigation. Prony was initially daunted by the task of calculating these tables (from the numbers 0 to 100,000 to nineteen decimal places, and the numbers from 100,000 to 200,000 to twenty-four decimal places). It was so immense that even all the mathematicians in France would not be able to complete it. What to do?

In a flash of inspiration after reading about the idea of "the division of labour" in Adam Smith's book "The Wealth of Nations," Prony saw that the job of compiling these tables could be divided up into two separate tasks: mechanical calculation, which did not necessarily require any previous math background, and verification or supervision, which required the skills of mathematicians. If he could train enough workers to grind out the mechanical calculations, relatively few mathematicians would be necessary to carry out the verification and supervision roles, and the job would be done that much sooner. Where to recruit these workers?

|

| Hairdressers, |

|

| ...plus Worksheets... |

The hairdressers could take the worksheets home, and when the work was done, they would bring them in to be checked by mathematicians. This is like the cottage industry of piecework sewing that can be completed at home and then brought in to a central location for inspection. In the book "When Computers Were Human," the author D.A. Grier says these trained computers were "little different from manual workers and could not discern whether they were computing trigonometric functions, logarithms, or the orbit of Halley's comet." This model of labour, armies of trained workers grinding out a product for higher ups, can be found today, not only in factories, but also in university graduate schools.

|

| ...equals Calculators... |

|

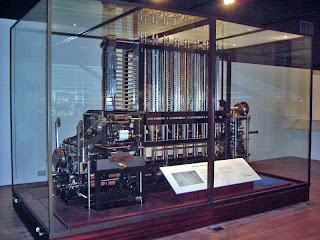

| ...and Computers. Babbage's Difference Engine #2, now at the Science Museum in London |